#1. 3rd day: A Challenge is a Chance – writing Hangul

The writing exercise.

Yesterday I was surprised that there are 8 vowel-characters in Hangul instead of 5. Today, I got another surprise: 6 more characters joined the group. I feel a bit confused as the 6 new characters represent the syllables ya, yu, two ye and two yo. On the one hand this looks to me like the combination of y as a consonant with the vowels a, u, e and o. On the other hand Hichol Cho talks about adding 点々 (dot dot) to the basic vowel strokes from yesterday. All the characters from last day’s lesson which had already one dot (or shorter stroke in the sans serif typeface) got a second one. And the characters for o and u which were based on 0 with a single stroke are excluded from this extension. This makes sense to me. The idea of adding dots (diacritics) to the vowels are anyway a familiar concept in German: a, u, o > ä, ü, ö.

While I was quite happy with this development as the exercises felt like a repetition of yesterday, I realised that the chapter was not yet over …

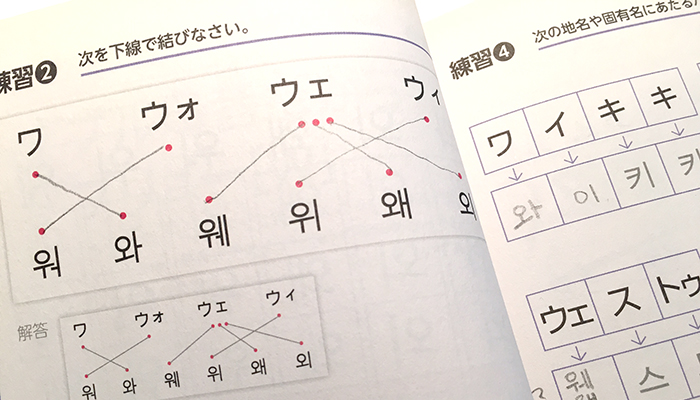

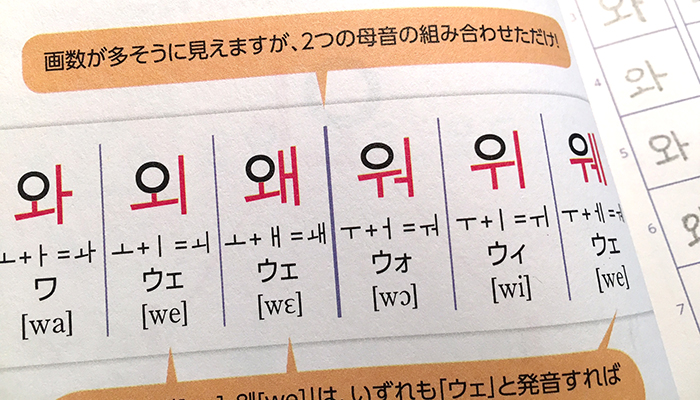

The next step was harder to understand. Another 6 vowels wanted to join the club and Hichol Cho calls them “double vowels”. For this as well the author provides a memory aid: double vowel > w. The w sound can be achieved by 오 (o) and by 우 (u). I found it very interesting that for the combination with a and e, 오 (o) is used and 우 (u) for o, i and e. Additionally the lower part of 오 (o) and 우 (u) is just reversed. Suddenly the characters look like indicators or markers to me.

And suddenly looking at this word 우유 (Milk) I started to see human shapes… (I am not drunk!)

But still the lesson had one more surprise to me, another vowel: 의

The horizontal stroke for u and the vertical for i form the 21st vowel, ui.

Who said Korean is simple?

Reading of the day.

The connection between the graphic representation of phonetics in Hangul made me curious yesterday and I wanted to know more. In my library I kept the book by Noma Hideki. The subheadline to his book The birth of Hangul says creating characters from phonetics. Noma seems to provide me some answers to my questions.

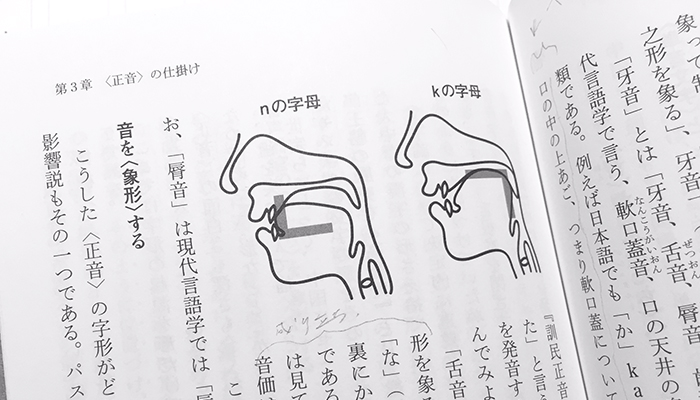

To my surprise Noma calls Hangul a pictographic system of characters. Pictographic – not in the sense of picturing the visible world – but picturing sounds. Sounds are not visible in a classic sense, they do not have a physical body. Instead of visualising the sounds, Hangul characters visualise how or where the sounds are created. More precisely the anatomy of the head (especially the organs involved while speaking) is analysed in regard of the creation of the different sounds. Roughly speaking – the shape and position of the tongue, the involvement of the teeth, the shape of the lips and whether the sound comes from the throat – all these were analysed and translated into abstract forms.

This is impressive and seems to demonstrate a special concept of visualisation. There is much more to discover.

Reference:

Noma Hideki: The birth of Hangul. [野間秀樹・ハングルの誕生] Heibonsha, 2010. 119–129.